News

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Long Term Physical and Mental Health

By Dr. Cathy Humikowski, Lurie Children’s Hospital Chicago

Early during my career as a pediatric intensive care physician, I admitted a little boy who had suffered severe neurologic injury during a police raid on his house, caught in the fray as three generations of his family struggled to hide from authorities. My job was not to understand why the raid took place at his house. My job was to help him recover (as well as possible) from the brain injury he sustained and then, if my team was successful, return him to that very same house.

At that point in my career, despite practicing at a Level I trauma center in one of the most violent and economically disadvantaged urban areas in the nation, I hadn’t formally learned about Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). I just knew, in some intrinsic visceral way, that this boy’s brain injury was not the biggest mountain he would have to climb.

ACEs are defined by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as “potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood.” Examples include exposure to violence in the home or community, personal experience with abuse or neglect, and household instability due to substance use, divorce, mental health problems or incarceration. Chronic food insecurity, unstable housing, or discrimination can bear similar impact as more overt traumatic experiences.

However salient this boy’s story remains in my memory, his struggles sadly are not unique. In a landmark study published by the CDC and Kaiser Permanente in 1998, more than 60% of adults reported experiencing at least one type of ACE in their lifetime and 1 in 6 reported they had experienced 4 or more types of ACEs. The study further identified a dose-response relationship between ACE exposure and a range of outcomes including substance use, depression, heart disease, stroke, diabetes, asthma, obesity, and cancer.

Growing research across the last quarter century has identified underlying mechanisms for these associations, including a biochemical basis for toxic stress. To understand toxic stress, recall any moment in which your own fight-or-flight mechanisms were activated: palms sweating, heart racing, muscles tensed. Now imagine this system activated chronically, exposing every cell in your body to dysregulated levels of adrenaline, cortisol, and pro-inflammatory signals on an ongoing basis. These biochemical features of toxic stress impact the nervous system, endocrine system, and immune function with downstream effects on attention, executive function, and impulsivity, contributing to dysregulated stress response across a lifespan.

Fortunately, research has also identified ways to mitigate the harmful impact of ACEs if they can’t be prevented. In the clinical environment where I work, trauma-informed care models are one way to improve outcomes. Trauma-informed care requires understanding how trauma impacts health, screening for exposure, addressing trauma-related health issues (including mental health), and linking families to protective support services in the community. This model takes effort, education, time, and resources—challenging in a time of financial strain across health systems—but it can reap lasting benefits for a lifetime.

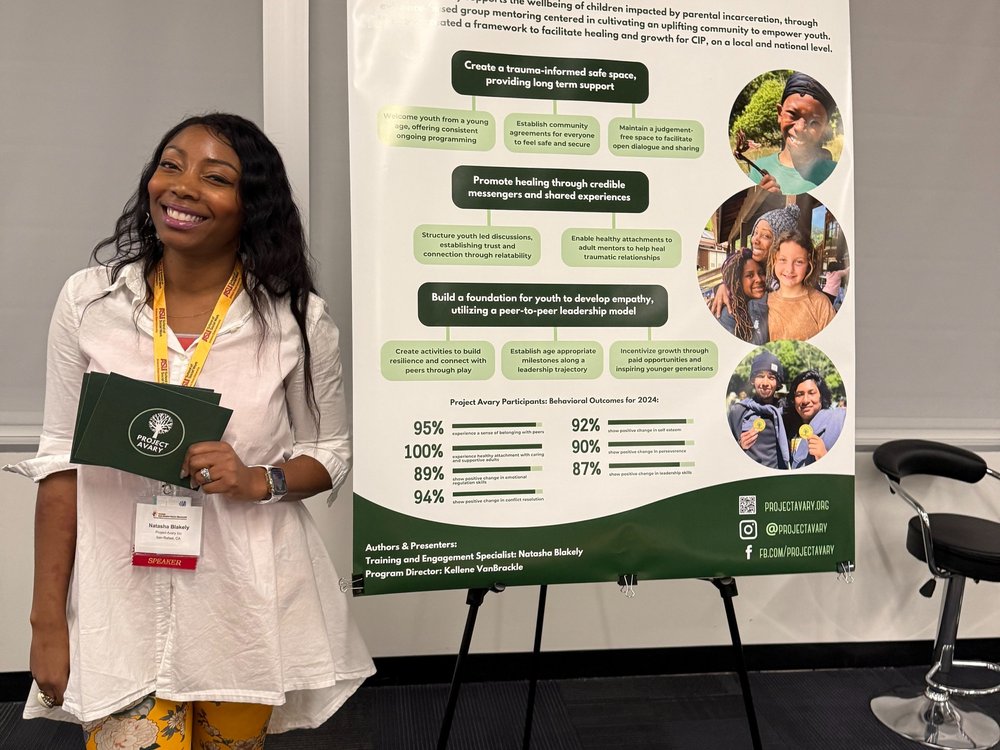

Outside the clinical environment—that is, in the wide-open world where children grow and develop—the most important protective factors include nurturing relationships, positive peer networks, and the stable presence of caring adults who can serve as mentors and role models. It’s astonishing to imagine that something as simple as a peer support group can mitigate the effects of toxic stress perpetuated by ACEs, but decades of research shows that it can.

The burden of childhood trauma can feel overwhelming, as it felt to me when I admitted that little boy whose life I could not save. But I have since learned (and strive to practice) trauma-informed care, and I have found opportunities to work with organizations like Rainbows for All Children. These experiences help silence that sense of inertia that leads to cynical nonaction, driven by the notion that nothing a single person can do will heal these wounds. Don’t believe that for one second. Just because you can’t do everything, doesn’t mean you can’t do anything.

Resources and Further Reading:

https://www.cdc.gov/aces/about/index.html

https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(98)00017-8/fulltext

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9173206

Cathy Humikowski is a pediatric intensive care physician practicing in Chicago. She writes and speaks about burnout, resilience, and secondary trauma. Her essays have been published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the New England Journal of Medicine, and the Chicago Tribune.